National Recovery Month – Updated for 2021: “Recovery is for Everyone: Every Person, Every Family, Every Community”

National Recovery Month – Updated for 2021: “Recovery is for Everyone: Every Person, Every Family, Every Community”

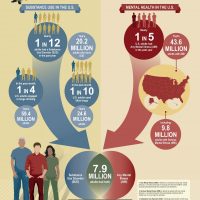

Substance use disorder (SUD) is an important issue that effects millions of people in the U.S. either directly or indirectly every day. Unless people receive treatment, the impact of SUD on the economic, social, work and relationships causes personal and financial hardships that can be life-altering, as illustrated in the Substance Use in the United States Infographic below.

With treatment and support, people diagnosed with SUDs can enjoy the same high quality of life as those without a SUD and it was to promote that kind of support for treatment and recovery that National Recovery Month was established 32 years ago. Recovery Month is all about celebrating the progress people in recovery have made, in the same way that we celebrate gains made by those who are managing other health conditions, including Hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and heart disease.

Recovery Month 2021 Theme

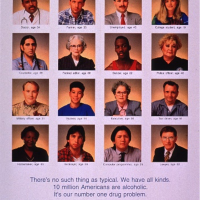

The Recovery Month 2021 theme is “Recovery is for Everyone: Every Person, Every Family, Every Community.” Some people may remember a poster published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) entitled “The Typical Alcoholic American” pictured below.

When we understand that there is no typical person with substance use disorder or mental illness, that the people who are in recovery are just like us: ourselves, our parents, our grandparents, our children, and are from all races, ethnicities, ages, and all walks of life professionally, then the theme makes sense. Recovery is for everyone because mental illness and addiction and the recovery so important to being healthy and enjoying a high quality of life is also for everyone. And support is needed from everyone for that to be accomplished.

Background and Definition of Recovery

OnDemand blog post for Recovery Month 2018, Supporting Recovery: What Recent Research Tells Us, provided SAMHSA’s working definition of Recovery. That blog post explained that the definition of recovery continues to evolve and expand. The article looked to the research base to inform us of how family and friends of those in recovery can best support them as they build their lives to achieve the same quality of life and fulfillment as those who have never had AOD problems. For Recovery Month 2020 we highlight some of the conditions and strategies that best support sustained, long-term recovery according to empirical evidence, and outline some important changes to the month-long event itself.

Meet the New National Recovery Month Sponsor!

National Recovery Month (Recovery Month) was sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) for 30 years. In June 2020, the Faces & Voices of Recovery assumed sponsorship. A new webpage was developed for Recovery Month as well as a recovery event calendar, free downloadable tools, and promotional items for sale. The Faces & Voices of Recovery main webpage is still the same, with many resources, recovery data, and the National Recovery Institute. One important feature of the National Recovery Month 2021 event calendar is that organizations can submit an event to be posted on the calendar. People searching for events to attend, or support can find them listed by City, State, event type, and event category, so registering on the Recovery month website is a great way to market your event.

SAMHSA Supports Recovery Month

SAMHSA remains a firm supporter of Recovery Month. For National Recovery Month 2020, SAMHSA hosted a Recovery Month Webinar Series. The series is still relevant and still available for viewing with the following topics:

- September 3, 2020: Integration of Medication-Assisted Treatment in Treatment and Recovery Support

- September 10, 2020: SAMHSA Transforming Lives Through Supported Employment

- September 17, 2020: Communities Supporting Recovery

- September 24, 2020: The Importance of Integrating Recovery Support Services: The Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic Model

SAMHSA’s Recovery and Recovery Support web page contains additional general information about recovery-oriented care and recovery support systems that help people with mental and substance use disorders manage their conditions successfully. SAMHSA also sponsors the SAMHSA Treatment Locator and helpline 1-800-662-HELP (4357) to help people access treatment services.

NIH and NIDA Support Recovery Month

The NIH About Recovery webpage describes recovery as “a process of change through which people improve their health and wellness, live self-directed lives, and strive to reach their full potential.” The site describes some types of recovery programs and offers a variety of resources for anyone working with patients entering recovery. The Drugs & the Brain Wallet Card is free and can be ordered in packs of 50. The card features information about brain structure and triggers and leaves blank spaces for individuals to write in their own triggers and resources in their area. Talking points on the science of drug use and other resources are available on the NIH The Science of Drug Use: Discussion Points webpage.

Factors and Supports Shown by Research to Contribute to Sustained, Long-term Recovery

The following are some of the resources and strategies that are supported for sustained, long-term recovery by research and that behavioral health providers can provide through services or through linkages and networks that are either available to them, or that they establish in the interest of providing a Recovery Oriented System of Care (ROSC):

Recovery capital – In Peer Recovery Support Workers: The Research Says “Yes!” this blog site touched upon the idea of recovery capital as it is explained in the “Building Recovery Capital” Slide Decks For You from the Mountain Plains Addiction Technology Transfer Center (ATTC) HHS Region 8. Recovery capital is “…the sum of resources necessary to initiate and sustain recovery from substance misuse (employment, school, housing, healthy family, etc.),” and improve quality of life for those in recovery (White 2004). According to Granfield & Cloud, recovery capital can be categorized in four broad domains: social, physical, human, and cultural capital (1999; Cloud & Granfield 2008). A study in Scotland that looked at the importance of recovery capital as a predictor of problem severity found that physical capital (economic and financial assets) and well as human capital (problem solving, self-efficacy, self-awareness, and self-esteem) was a predictor of problem severity (Burns and Marks, 2013).

Recovery Supports – “Even after a year or 2 of remission is achieved…it can take 4 to 5 more years before the risk of relapse drops below 15 percent, the level of risk that people in the general population have of developing a substance use disorder in their lifetime. As a result, like other chronic conditions, a person with a serious substance use disorder often requires ongoing monitoring and management to maintain remission and to provide early re-intervention should the person relapse. Recovery support services refer to the collection of community services that can provide emotional and practical support for continuing remission as well as daily structure and rewarding alternatives to substance use (U.S. HHS, 2016).

The Mountain Plains ATTC provides an online video Building Recovery Capital through Digital Health Technologies that showcases the use of digital health technologies for building recovery capital as part of a ROSC. According to the ATTC definition: “A ROSC is a coordinated network of community-based services and supports that is person-centered and builds on the strengths and resiliencies of individuals, families, and communities to achieve abstinence and improved health, wellness, and quality of life for those with or at risk of alcohol and drug problems” (ATTC Network, 2019). Recovery supports can include the following:

Mutual aid groups – The best known and longest existing group is Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) founded in 1935 (U.S. HHS, 2016). 12-step groups are the most widely available pathways to recovery, are peer-facilitated, and are available for friends and family. 12-step groups are particularly well attended when the concept is introduced and discussed with a healthcare professional (U.S.HHS, 2016).

Supported Recovery Housing – One of the strongest themes in a British qualitative study of 45 participants from 11 treatment facilities in Northern England was that of the importance of supported housing and the ability to acquire it through financial independence or welfare. The study used semi-structured qualitative interviews of 30-90 minutes in duration to examine recovery capital factors perceived to be either barriers or facilitators of sustained recovery post treatment (Duffy & Baldwin, 2013). Results of a retrospective analysis of records of a residential housing program in Brazil suggested that supported housing, when combined with urine testing, abstinence rates were significantly higher during the recovery period immediately following detoxification, and employability increased (do Carmo, et al., 2018). A Texas descriptive study of ten recovery homes in Texas that provided both treatment and peer support through a variety of recovery models noted that there is a dearth of studies of recovery housing in the U.S. and no standardization of features or analysis of what types of living facilities or neighborhoods might best support treatment and recovery. As future studies emerge, more will be known about what types of recovery residences meet the needs of those in recovery, how to make it affordable for them, and most importantly, a comprehensive and standardized system for assessing such housing (Mericle, et al., 2017).

Recovery Community Centers – Recovery community centers differ from professional treatment centers in that they are peer-led, those who use these centers are “peers” or “members” and staff are referred to as “peer leaders” or “recovery mentors” (U.S. HHS, 2016). Recovery Community Centers are a relatively new concept and have not been empirically studied to show conclusively that they are effective. Future research will determine if this type of support outside of the clinical treatment domain is effective.

Recovery-based Education – For high school and college students navigating recovery can be a challenge due to factors such as substance use or perceived use by other students, pressure from friends and others to use substances, and availability of alcohol and other drugs. Multiple studies show that abstinence rates are lower for students after enrolling in a recovery high school and although research is limited, current results show some effectiveness in assisting with recovery. Collegiate recovery programs are becoming more widely established and offer a variety of recovery supports that are shown to be effective. A few of the services that many programs offer are residence halls of sections dedicated to students in recovery, counseling services, support groups and 12-step meetings, and help with mental health issues such as depression and eating disorder. Again, while results of studies to date are promising, more research is needed (U.S. HHS, 2016).

Relationships and Positive Social support – Social relationships, particularly re-building relationships with family and children is an important motivator for those entering and maintaining recovery (Duffy & Baldwin, 2013). In fact, one study found that while family and social relationships are one of the top three priorities for those with less than six months of abstinence, as the length of time in abstinence grows, this importance increases in priority by about five percent for those with more than three years of abstinence (Laudet & White, 2009). Those with substance use disorders (SUDs) not only often lack social support but often have negative relationships that can include isolation, domestic violence, or marital problems (Farris & Fenaughty, 2002). Learning to develop healthy relationships can be accomplished through supported recovery housing, recovery community centers, and through mutual aid groups such as 12-step groups (U.S.HHS, 2016). The importance of recognition from peers and treatment providers within treatment programs and 12-step groups has been established (Moos, 2008). In one recent narrative study the participants reported that social relationships apart from treatment helped just as much in their successful recovery (Pettersen et al., 2019).

Early and Ongoing or Continuing Treatment Some of the research that speaks to treatment modalities that are effective in promoting sustained, long-term recovery support the idea that the long-term benefits of brief interventions are minimal and that repeated episodes of care best serve to underscore the chronic nature of addition. Brief interventions are most appropriate and useful for initiating change or entry and/or re-entry into treatment, but do not contribute significantly to sustained, long-term recovery. Finally, those who receive treatment sooner and who receive more treatment are more likely to achieve sustained, long-term recovery. Therefore, there is a need for developing and evaluating approaches that emphasize continuing care (Godley et al., 2002; McKay, 2001) and long-term recovery management (Dennis, Scott, & Funk, 2003).

In addition to focusing more on continuing care and long-term recovery management, research supports the following strategies as being critical to sustained, long-term recovery: treatment of multiple substance use, integration with health care systems, and the criminal justice system (Rounsaville et al., 2003; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2002; Watkins et al., 2003; Weisner et al., 2001; Mertens et al., 2003; Scott et al., 2003; and Zanis et al., 2003

Recovery Coaching, Aftercare, or Long-term Recovery Management – These modalities include self-help groups, meaningful activities, peer networks, and providing daily structure. Research into aftercare services supports reduction of substance use, delayed relapse, reduced stress and improved quality of life (Arbour, Hambley, & Ho, 2011; Sannibale, Hurkett, Ban den Bossche, et al., 2003).

Peer Recovery Support Workers – Peer-based recovery support is the process of giving and receiving non-professional, non-clinical assistance to achieve long-term recovery from severe alcohol and/or other drug-related problems. This support is provided by people who are experientially credentialed to assist others in initiating recovery, maintaining recovery, and enhancing the quality of personal and family life in long-term recovery. To learn how community organizations provide peer support services to people in recovery and the importance of peer specialists in the behavioral health field, visit SAMHSA’s Peer Support Recovery Is the Future of Behavioral Health webpage.

For behavioral health providers who are interested in ways of understanding and measuring individual recovery pathways, read Measuring an individual’s recovery barriers and strengths written by David Best, Michal Edwards, Adam Mama-Rudd, Ivan Cano and John Lehman in Addiction Professional, November 1, 2016.

In observing Recovery Month 2021 we can remember that there are many ways of celebrating recovery. For those in recovery, it is important to honor progress made, for as White quotes Brooke Feldman in Amplified Recovery: “The greatest wisdom there is to be won comes from the places and spaces where we’ve been split and undone.” Friends and family may observe Recovery Month by doing some of the things to support recovery of their loved one that are mentioned in the blog post for Recovery Month 2018: Supporting Recovery: What Recent Research Tells Us. For behavioral health providers it might mean implementing some of what research shows is effective in supporting sustained, long-term recovery. You might take and have staff take the 100-item test created by William L. White: What is Your recovery Quotient? Toward Recovery-focused Education of Addiction Professionals and Recovery Support Specialists to get an idea of how fluent you and your organization are in the language of recovery. And be sure to check out the National Recovery Month website to find even more ways to observe Recovery Month 2020 to increase awareness and understanding of mental and substance use disorders. The theme for 2020 National Recovery Month is Join the Voices for Recovery: Celebrating Connections. The following are just of few of the many resources available for supporting sustained, long-term recovery. More resources can be found on the CASAT OnDemand Resources and Downloads section.

Recovery Month Links:

Website: 2021 National Recovery Month

![]() 2021 National Recovery Month on Facebook

2021 National Recovery Month on Facebook

![]() 2021 National Recovery Month on Twitter

2021 National Recovery Month on Twitter

![]() 2021 National Recovery Month on Instagram

2021 National Recovery Month on Instagram

ATTC resources links:

Anti-Stigma Toolkit: Guide to Reducing Addiction-Related Stigma:

The Art of Building Collaborative and Effective Partnerships with Faith Communities; Presenter: Rev. Robin Barnet (February 13th, 2019) Webinar Power Point Presentation

Best Practices in Recovery Oriented Systems of Care: The Case of Pioneer Human Services (Webinar)

Building Recovery Capital through Digital Health Technologies – Online Video Series:

Recovery-Oriented Systems of Care (ROSC) PSA

Recovery Monograph Series – William White’s Monograph Series is available now available in two volumes. Both volumes are available for purchase in soft cover and for download onto e Readers

Websites:

Faces & Voices of Recovery is dedicated to organizing and mobilizing the over 23 million Americans in recovery from addiction to alcohol and other drugs, our families, friends and allies into recovery community organizations and networks, to promote the right and resources to recover through advocacy, education, and demonstrating the power and proof of long-term recovery.

The Association of Recovery Schools (ARS): The Association of Recovery Schools is a registered 501(c) 3, nonprofit organization comprised of recovery high schools as well as associate members and individuals who support the integral growth of the recovery high school movement.

SAMHSA’s Recovery Support Strategic Initiative: Recovery-oriented care and recovery support systems help people with mental and substance use disorders manage their conditions successfully.

How will you or your organization celebrate National Recovery Month 2021? Please share the details in the comments section.

This article was developed by Stephanie Asteriadis Pyle, PhD at CASAT, feel free to use this information. A link to our site and attribution would be much appreciated. Suggested citation:

Pyle, S. (2021, August 25). National recovery month – updated For 2021: “Recovery is for EVERYONE: Every person, every family, Every Community”. CASAT OnDemand. https://casatondemand.org/2021/08/25/national-recovery-month-updated-for-2021-recovery-is-for-everyone-every-person-every-family-every-community/.

References

Ashford, R., Lynch, K., & Curtis, B. (2018). Technology and social media use among patients enrolled in outpatient addiction treatment programs: Cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(3), e84-e84. doi:10.2196/jmir.9172

Burns, J., & Marks, D. (2013). Can recovery capital predict addiction problem severity? Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 31(3), 303-320. doi:10.1080/07347324.2013.800430

Cano, I., Best, D., Edwards, M., & Lehman, J. (2017). Recovery capital pathways: Modelling the components of recovery wellbeing. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 181, 11-19. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.002

Cloud, W, & Granfield, R., Subst Use Misuse. 2008; 43(12-13): 1971–1986. doi:10.1080/10826080802289762

Campbell, W., Hester, R., Lenberg, K., & Delaney, H. (2016). Overcoming addictions, a web-based application, and SMART recovery, an online and in-person mutual help group for problem drinkers, part 2: Six-month outcomes of a randomized controlled trial and qualitative feedback from participants. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(10), e262-e262. doi:10.2196/jmir.5508

do Carmo, D. A., Palma, S. M. M., Ribeiro, A., Trevizol, A. P., Brietzke, E., Abdalla, R. R., . . . Ribeiro, M. (2018). Preliminary results from brazil’s first recovery housing program. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 40(4), 285-291. doi:10.1590/2237-6089-2017-0084

Duffy, P., & Baldwin, H. (2013). Recovery post treatment: Plans, barriers and motivators. Substance Abuse Treatment Prevention and Policy, 8(1), 6-6. doi:10.1186/1747-597X-8-6

Farris, C. A., & Fenaughty, A. M. (2002). Social isolation and domestic violence among female drug users. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 28(2), 339-351. doi:10.1081/ADA-120002977

Granfield, R., & Cloud, W. (1999). Coming Clean: Overcoming Addiction without Treatment. New York: New York University Press.

National Institutes of Health (U.S.). Medical Arts and Photography Branch. United States. Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration. Office for Substance Abuse Prevention.

National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information (U.S.). 1991. The typical alcoholic American. Bethesda, Md. http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101450055

Kaskutas, L. A., Borkman, T. J., Laudet, A., Ritter, L. A., Witbrodt, J., Subbaraman, M. S., … Bond, J. (2014). Elements that define recovery: the experiential perspective. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 75(6), 999–1010. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.999

Laudet, A. B., Ph. D, & White, W., M.A. (2010). What are your priorities right now? identifying service needs across recovery stages to inform service development. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 38(1), 51-59. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2009.06.003

Mericle, A. A., Polcin, D. L., Hemberg, J., & Miles, J. (2017). Recovery housing: Evolving models to address resident needs. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 49(4), 352-361. doi:10.1080/02791072.2017.1342154

Moos, R. H. (2008). Active ingredients of substance use-focused self-help groups. Addiction, 103(3), 387-396. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02111.x

Pettersen, H., Landheim, A., Skeie, I., Biong, S., Brodahl, M., Oute, J., & Davidson, L. (2019). How social relationships influence substance use disorder recovery: a collaborative narrative study. Substance abuse: research and treatment, 13, 1178221819833379.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Substance_use_%26_mental_illness_in_US_adults_18_years_and_older.jpg – SAMHSA, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General, Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: HHS, November 2016.

Blog Post Tags:

Related Blog Posts

Related Learning Labs

Related Resources

.

- Buscar Tratamiento de Calidad para Trastornos de uso de Sustancia (Finding Quality Treatment for Substance Use Disorders Spanish Version)

- Finding Quality Treatment for Substance Use Disorders

- Focus On Prevention: Strategies and Programs to Prevent Substance Use

- Monthly Variation in Substance Use Initiation Among Full-Time College Students

- The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Report: Monthly Variation in Substance Use Initiation Among Adolescents