Coping with a Pandemic:

Coping with a Pandemic:

How Behavioral Health Providers Can Help Clients with Mental and Substance Use Disorders Meet the Challenges of COVID-19

Overview of the Problem

Today the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic, meaning that it is likely to spread to all countries in the world (STAT, March 11, 2020). “We expect to see the number of cases, the number of deaths, and the number of affected countries climb even higher,” said Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

Since the first case of COVID-19 was identified in the U.S., increasing numbers of people are being exposed, but not necessarily to the virus. They are being exposed to the unintended consequences that often accompany measures that are taken to reduce or prevent an outbreak. As people attempt to understand what they need to do to protect themselves and their loved ones, and the implementation of measures such as mass and individual quarantines, “new rules” about interactions in schools, workplaces, and socially, the media hype that naturally occurs during epidemics or natural disasters, and the misinformation that is invariably spread all generate a different kind of epidemic. The “other” epidemic consists of fear, anxiety, stigma that are out of proportion to the actual risk. Fueled by feelings of isolation, panic, and loss of control, the results can be irrational and unnecessary behaviors, such as self-quarantining without meeting criteria for quarantine, social shunning, threats, loss of employment, and even violence.

Brief History, Symptoms, Treatment, and Prognosis

COVID-19 is believed to have developed in China near the end of 2019 in a “wet market”, a collection of stalls selling fish, meat, and wild animals. The first people to contract the disease had all been connected to the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan China. At this writing, there are 121,564 total confirmed cases worldwide with a total of 4,373 deaths.

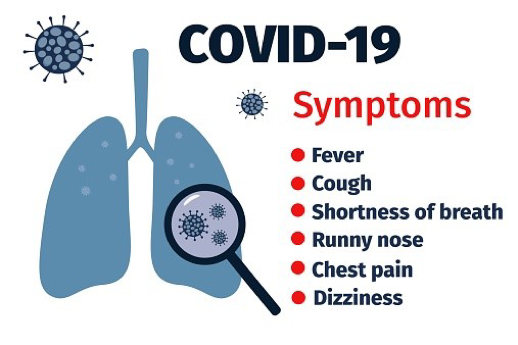

Figure 1. Symptoms may appear in as few as 2 days or as long as 14 days after the exposure of the virus (CDC, 2020). For more information: Nevada’s Response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For most people, COVID-19 usually manifests as a mild respiratory infection in an estimated 80% of those infected, with about 50% contracting pneumonia. For an additional 15% the illness becomes severe, with 5% requiring critical care. While the outbreak numbers are still climbing in the rest of the world, in China, where COVID-19 originated, the disease already appears to be waning, with just 24 new cases confirmed yesterday (STAT, 2020).

How the COVID-19 Outbreak Can Affect Those with Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders

There are similarities in this outbreak to the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak of 2003, which was caused by a different coronavirus that killed 349 of 5327 patients who had confirmed infections in China (Xiang, et al., 2014). In Toronto, Canada during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak, for instance, there was stigma and social shunning. People were discriminated against at work, their property was attacked and some Asians reported being denied rides on public transportation or cabs. This is most likely the direct result of feelings of anxiety and fear about a perceived threat to the health and well-being of themselves or those they love.

During an infectious outbreak or disaster, people have five basic emotional needs: to feel safe, calm, connected; to feel a sense of efficacy; and to feel hope (Howe, 2011 as cited in Papadimos et al., 2018). For people diagnosed with behavioral health and substance use disorders, coping with an infectious disease outbreak can be even more of a challenge and can even precipitate a crisis.

How Behavioral Health Providers Can Help

While some anxiety can be useful as motivators for people to learn about the threat and take appropriate precautions, too much anxiety can be a problem for those who have anxiety, depression or other mental health disorders.

- Prepare clients to help themselves. The best antidote to fear is accurate information about the disease from credible sources. Some of those sources are listed below under “Resources.” Behavioral health providers may want to have links or materials handy.

- Bring the topic to the level of conversation during regularly scheduled appointments. Checking in about the issue and how it is affecting them or their loved ones is always a good idea. If it is not a problem no harm is done. If it is a problem it may reduce stress and anxiety to help clients plan for what they will do if they are exposed and must be quarantined, for instance. People who are not prepared may experience irritability, violent thoughts or behaviors, or a relapse may be triggered.

- Timely healthcare is vital. Despite the fact that people may fear the effects of being infected or may want to avoid quarantine and the isolation, boredom, and loss of income it may bring, people need to be treated as soon as possible to avoid complications (Xiang, et al., 2020).

- Brush up on crisis interventions if that isn’t something you have recently provided. Arrange referral sources ahead of time if necessary. Tips for Health Care Practitioners and Responders: Helping Survivors Cope with Grief After a Disaster or Traumatic Event is a great resource.

- Hotline numbers are very useful for people in crisis. Refer clients and their families to those you know about in case they need a crisis intervention. Additional hotline numbers are listed below.

- Include children and help clients to address the topic with their children. The need to reassure their children may even help motivate parents to model healthy self-care practices. A booklet with tips is in the resources below.

- Develop guidelines for self-support, peer support, and support for healthcare professionals as well as counseling clients so they can develop coping skills and develop resilience.

- Include stress relief, breathing, yoga, and other self-calming strategies, or review those strategies if they are already a part of their treatment plan.

- Screen for depression, anxiety, and suicidality if appropriate. A negative screening result can be reassuring for clients and a positive one can identify potential problems.

- Because of the potential for quarantine, help clients to do what they can to prepare their environments. This can include providing smartphone and computer apps that will be useful if they feel isolated and can also be used as alternative ways to maintain contact with friends and loved ones without risk of exposure.

Resources:

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) links:

- News articles:

- CDC, FDA, HHS: The federal agencies fighting the coronavirus – This article outlines the federal agencies that are fighting COVID-19

- Nevada Links:

- Nevada’s Response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus

- Crisis Support Services – 1-800-273-8255

- Johns Hopkins Interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19:

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administrations (SAMHSA):

- Coping with Stress During Infectious Disease Outbreaks

- Talking with Children: Tips for Caregivers, Parents, and Teachers During Infectious Disease Outbreaks

- Tips for Health Care Practitioners and Responders: Helping Survivors Cope with Grief After a Disaster or Traumatic Event

- Disease Outbreak resource page

- Taking Care of Your Behavioral Health During an Infectious Disease Outbreak Tips for Social Distancing, Quarantine, and Isolation

- CHEST Foundation: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) – This page provides excellent information about the main feature of COVID-19 that causes acute illness and how it can be treated:

- World Health Organization (WHO): WHO: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- The Lancet article Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed

- Medscape article Coronavirus: Mass Quarantine May Spark Irrational Fear, Anxiety, Stigma

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline – 1-800-273-8255

Do you have additional resources to add to this list?

Please share your links or resources in the comments!

References

Cutter, C., & Feintzeig, R. (2020, Mar 08). Corporate america races to respond to a crisis that upends work; employers separate their teams, require personal travel disclosures and offer cash for supplies. Wall Street Journal (Online) Retrieved from http://unr.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.unr.idm.oclc.org/docview/2373507151?accountid=452

Dong, E., Du, H., & Gardner, L. (2020). An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1

Howe EG: How can care providers most help patients during a disaster? J Clin Ethics 2011; 22:3–16.

Megan Brooks. Medscape Medical News. Psychiatry News. Coronavirus: Mass Quarantine May Spark Irrational Fear, Anxiety, Stigma. January 28, 2020. Retrieved 3.09.2020.

Papadimos, T. J. , Marcolini, E. G. , Hadian, M. , Hardart, G. E. , Ward, N. , Levy, M. M. , Stawicki, S. P. & Davidson, J. E. (2018). Ethics of Outbreaks Position Statement. Part 2. Critical Care Medicine, 46(11), 1856–1860. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003363.

Xiang, Y., Yu, X., Ungvari, G. S., Correll, C. U., & Chiu, H. F. (2014). Outcomes of SARS survivors in china: Not only physical and psychiatric co-morbidities. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry, 24(1), 37-38.

Xiang, Y., Yang, Y., Li, W., Zhang, L., Zhang, Q., Cheung, T., & Ng, C. H. (2020). Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(3), 228-229. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8

Blog Post Tags:

Related Blog Posts

Related Learning Labs

Related Resources

.

- Buscar Tratamiento de Calidad para Trastornos de uso de Sustancia (Finding Quality Treatment for Substance Use Disorders Spanish Version)

- Finding Quality Treatment for Substance Use Disorders

- Focus On Prevention: Strategies and Programs to Prevent Substance Use

- Monthly Variation in Substance Use Initiation Among Full-Time College Students

- The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Report: Monthly Variation in Substance Use Initiation Among Adolescents

Such great information and perspective!

Glad you liked it 🙂