“The behavioral risk taking that occurs during adolescence can profoundly impact immediate and long-term health outcomes” (Clements-Nolle & Rivera, 2013).

Introduction

The 2019 Nevada Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) is being administered at high school and middle schools throughout Nevada this spring. A collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Nevada Department of Education, and the State of Nevada Division of Health and Human Services, the YRBS has been administered biennially by the School of Community Health Sciences at the University of Nevada, Reno since 2013. The YRBS collects information on a variety of adolescent health behaviors including risk factors related to substance use and mental health (behavioral health). The survey instrument was designed by the CDC in cooperation with other federal agencies and state and local education and health departments, and has been administered to Nevada high school students since 1993. For a complete list of all questions that have been included in the YRBSS over the years, see the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) YRBS Questionnaire content 1991-2019.

Known as the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) at the national level, the survey was initiated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1990 to monitor the health behaviors among youth that contributed to the leading causes of morbidity, mortality, disability, and social problems in the United States. (The CDC uses the acronym YRBSS for Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS), whereas Nevada has shortened the title to the Nevada Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Nevada YRBS). Additional information about the YRBSS can be found at: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). )The health behaviors and other indicators monitored by the YRBSS are highlighted below (Table 1). The CDC uses the YRBSS data to determine the prevalence of health behaviors among our nation’s youth, monitor trends over time, examine co-occurrence of behaviors, provide comparable data at the national, state, territorial, tribal, and local levels and among subpopulations of youth, and monitor progress toward Healthy People Objectives (CDC, 2018).

Introduced in 1971, the Healthy People (HP) initiative serves as a public health road map and compass for United States population (Koh, 2014). Every ten years, Healthy People establishes health benchmarks and sets targets for the coming decade to improve the nation’s health. HP’s goal is to not only reduce morbidity and mortality in the U.S., but also improve quality of life for all Americans. See Table 1 for health and social problems (immediate and longer-term) that can result from engaging in the health risk behaviors monitored by the YRBS and YRBSS.

Since its inception in 1993, Nevada’s substance abuse prevention and public health professionals, educators, and decision-makers have come to rely heavily on the YRBS at the state and local levels for program planning and evaluation. To ensure a more accurate reflection of Nevada’s rural and frontier populations, the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR) data includes regional weighting. For the 2013-2017 Nevada YRBS reports, the CDC and UNR prevalence estimates may differ slightly because the CDC data are weighted at the state level. For local comparisons, the Nevada reports prepared by UNR are recommended.

“Nationally, the YRBS has become the primary source of information on the most important health risk behaviors of high school students and is increasingly used by leading educators, public health officials, and others to improve school health policies and programs.” University of Nevada Reno, School of Community Health Sciences, Nevada Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Introduced in 1971, the Healthy People (HP) initiative serves as a public health road map and compass for United States population (Koh, 2014). Every ten years, Healthy People establishes health benchmarks and sets targets for the coming decade to improve the nation’s health. HP’s goal is to not only reduce morbidity and mortality in the U.S., but also improve quality of life for all Americans. See Table 1 for health and social problems (immediate and longer-term) that can result from engaging in the health risk behaviors monitored by the YRBS and YRBSS.

Why Monitor Adolescent Risk Behaviors?

Healthy People (HP) 2020 defines adolescents as ages 10 to 17 and young adults as ages 18 to 25. Multiple health and social problems may start or peak during adolescence and young adulthood. Consequently, adolescence is a critical period in human development that has far reaching consequences for an individual’s morbidity and mortality across the lifespan (World Health Organization (WHO), 2019). According to Kristen Clements-Nolle PhD, MPH and Carina Rivera, MPH, of the University of Nevada, Reno, “The transition from childhood to adulthood (adolescence) is a period of rapid physical, emotional, and developmental change. Adolescence is a time when many health problems are first identified and many health behaviors, both positive and negative, are established,” (Clements-Nolle & Rivera, 2013).

In their 2013 review of the epidemiology of adolescent health,

Clements-Nolle and Rivera concluded that most adolescent health problems are preventable which has important implications for public health and prevention. The researchers reviewed behavioral health indicators related to the following five areas: (1) chronic disease, (2) mental health and suicide, (3) substance use, (4) sexual health, and (5) injury and violence.

Table 1: Risk behaviors, Health, and Social Problems among Adolescents in the United States

YRBSS Health Risk Behaviors and Indicators Monitored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (CDC, 2018)

- Unintentional Injuries and Violence

- Tobacco Use

- Alcohol and Other Drug Use

- Sexual Behaviors

- Dietary Behaviors

- Physical Activity

- Obesity, Overweight, and Weight Control

- Other Health Topics (Asthma, Oral Health Care, Sleep, Sun Safety, and Food Allergies)

Health and Social Problems among Adolescents Identified by the Healthy People (HP) Initiative (HP 2020)

- Mental disorders

- Substance use

- Smoking/nicotine use

- Nutrition and weight conditions

- Sexually transmitted infections, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- Teen and unintended pregnancies

- Homelessness

- Academic problems and dropping out of school

- Homicide

- Suicide

- Motor vehicle collisions

Understanding risk factors is also critical for effective prevention and early intervention for adolescent problem behaviors such as substance abuse, delinquency, teen pregnancy, school drop-out, and violence (Hawkins and Catalano, 2005). It can be difficult to evaluate individual intervention programs for their impact on the prevalence of risk factors over time. However, it is important to note that from 2007 to the present Nevada has been engaging in the best practice of addressing substance misuse prevention through the implementation of comprehensive prevention strategies across the lifespan and the use of evidence-based programming. For more on substance use prevention see our previous blog post, “Why does National Prevention Week Occur in May?” For informative infographics related to global adolescent health see the World Health Association (WHO)

Nevada Adolescent Health Risk Behavior Data

The 2017 YRBS data was made public in the summer of 2018. A review of the response trends for the past decade provides context for the 2017 data and informs future prevention and intervention efforts. The University of Nevada, Reno College of Community Health Sciences recently published 2017 Nevada High School CDC YRBS 10 Year Trends. (Trend data is also available directly from the CDC by downloading the data files or using the interactive Youth Online Data Analysis Tool.) The 10-year trend data shows that Nevada has made significant progress in the reduction of youth alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use consumption over the past decade, with two notable exceptions: marijuana use and the introduction of electronic nicotine delivery systems, or vaping.

Areas of Success

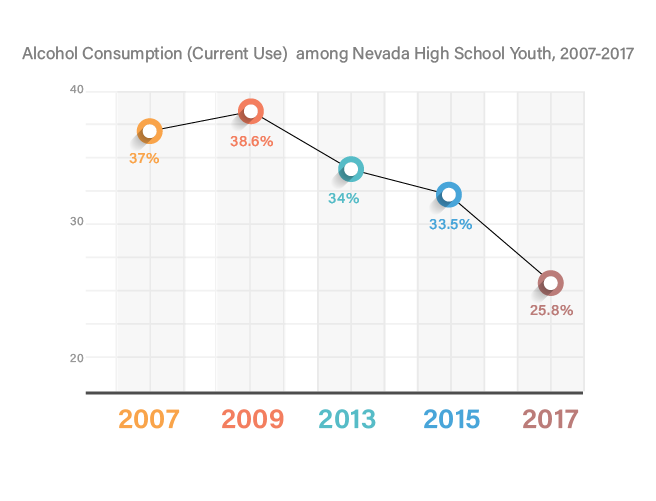

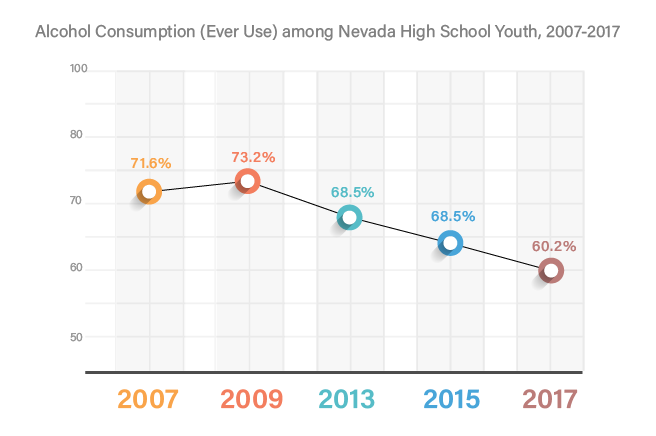

Nevada has made substantial advancement in the reduction of youth alcohol consumption over the past decade. In 2007 the percentage of Nevada high school youth who reported ever consuming alcohol was 71.6%. By 2017 this rate had been reduced to 60.2%. The percent of youth who reported current consumption of alcohol (within the past 30 days before the survey) declined steadily from 37% in 2007 to 25.8% in 2017 (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Alcohol Consumption (Current Use) among Nevada High School Youth, 2007-2017

Source: Nevada Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Tobacco Use among Nevada High School Youth

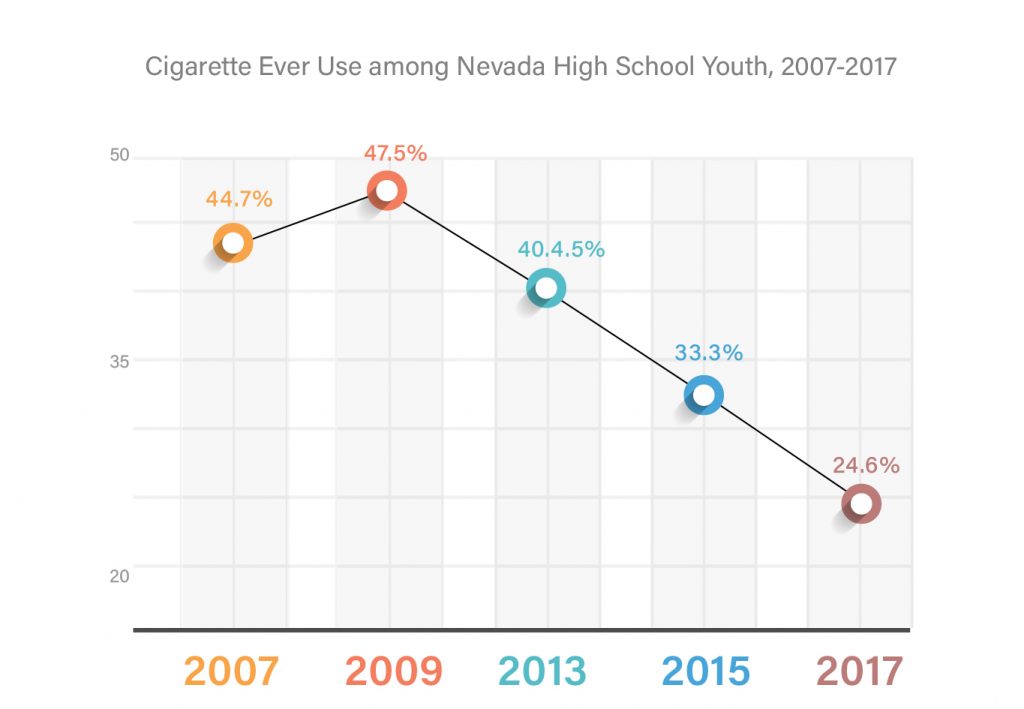

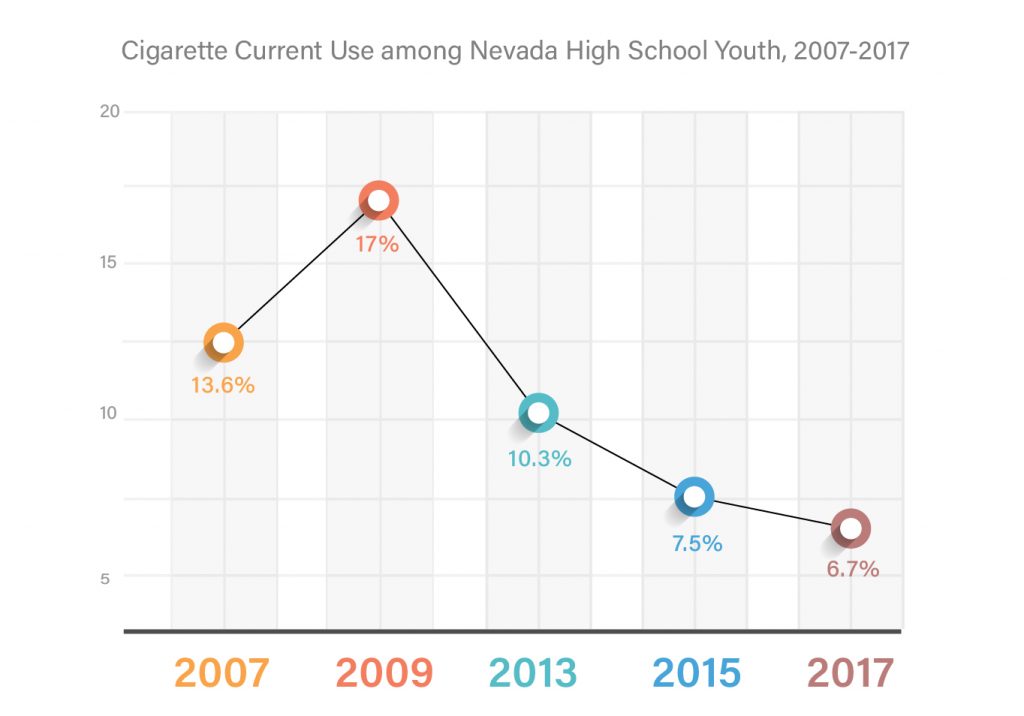

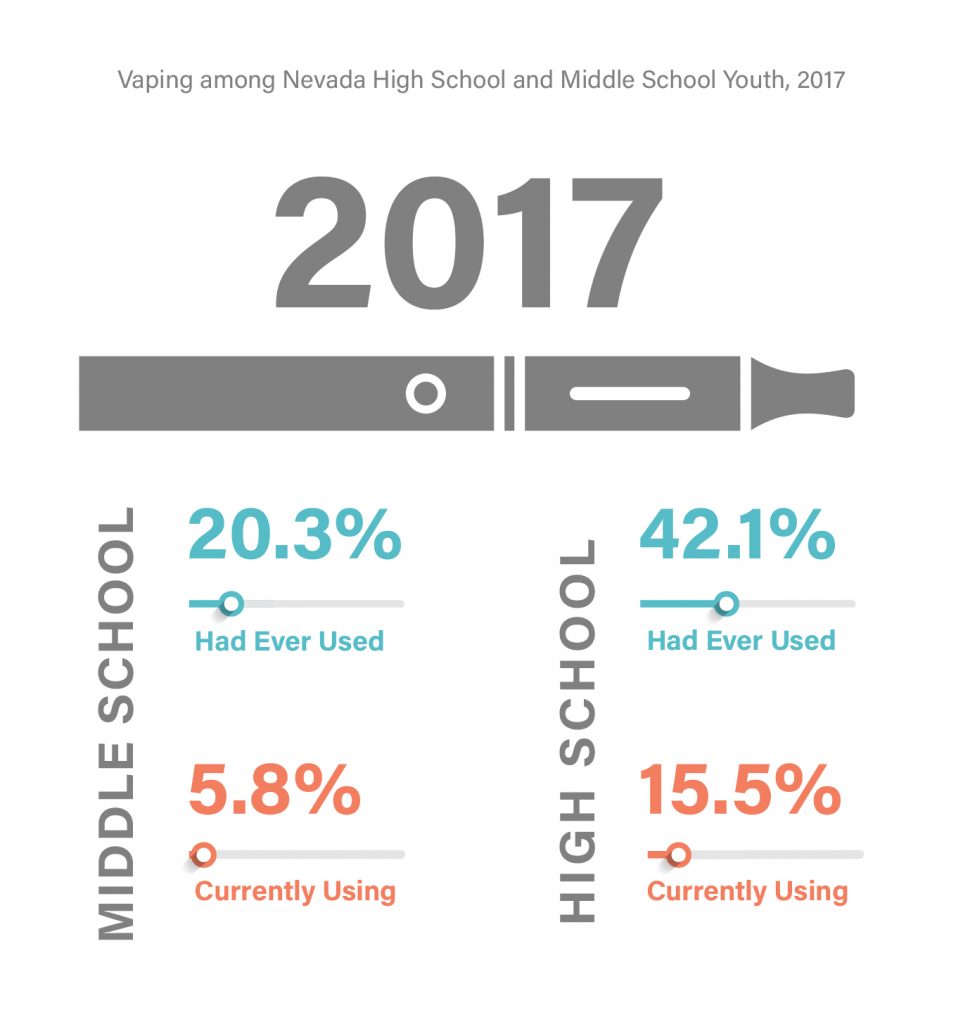

Nevada, along with the nation, has made noteworthy progress in reducing youth use of tobacco, particularly in terms of cigarette use (see Figures 3 and 4). Unfortunately, the popularity of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDs), or vaping, threatens to undermine the progress made in the past decades (Figures 5 and 6). According to the Surgeon General of the United States, “E-cigarette use poses a significant – and avoidable – health risk to young people. Besides increasing the possibility of addiction and long-term harm to brain development and respiratory health, e-cigarette use may also lead to the use of regular cigarettes that can do even more damage to the body” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018).

Figure 2: Alcohol Consumption (Ever Use) among Nevada High School Youth, 2007-2017

Figure 3: Cigarette (Ever Use) among Nevada High School Youth, 2007-2017

Source: Nevada Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Figure 4: Cigarette (Current Use) among Nevada High School Youth, 2007-2017

Source: Nevada Youth Risk Behavior Survey

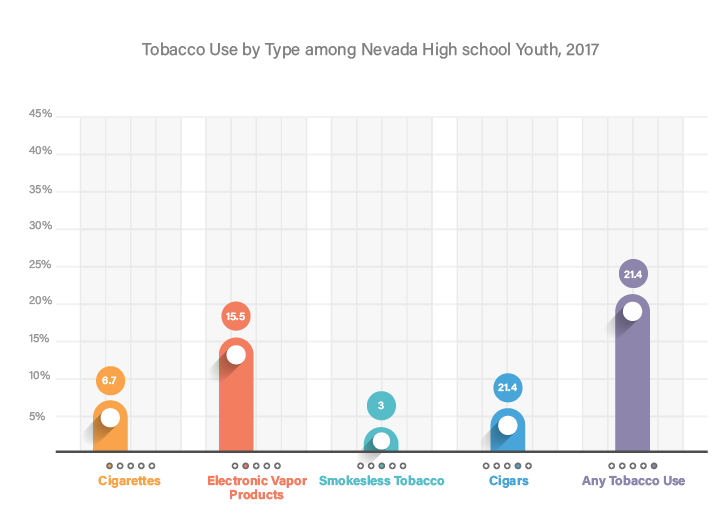

Figure 5: Snapshot – Tobacco Use by Type (Current Use) among Nevada High school Youth, 2017

Source: Nevada Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2017

Figure 6: Snapshot – Vaping among Nevada High School and Middle School Youth, 2017

Source: Nevada Youth Risk Behavior Survey

According to the Truth Initiative (formerly the American Legacy Foundation established via the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement in 1998), by 2018, “In just two years on the market, JUUL, a new type of e-cigarette, ha[d] become so popular among young people that it ha[d] already amassed nearly half of the e-cigarette market share. The product’s quick rise in popularity prompted The Boston Globe to call it ‘the most widespread phenomenon you’ve likely never heard of.’”

It is important to note that the 2017 YRBS did not included the term “juul” in questions about use of electronic vapor products. Thus the 2017 results may reflect an underrepresentation of actual tobacco and nicotine consumption by adolescents, via ENDS. Adolescent use of ENDS has been declared a national epidemic and the term “juuling” has been added to adolescent vernacular. Juuls, which resemble USB flash drives, do not look like traditional electronic cigarettes, and it is possible that adolescents view them in a different category than traditional e-cigarettes and electronic vapor products.

The following language has been included in the 2019 Nevada YRBS: “The next 5 questions ask about electronic vapor products, such as JUUL, Vuse, MarkTen, and blu. Electronic vapor products include e-cigarettes, vapes, vape pens, e-cigars, e-hookahs, hookah pens, and mods (Nevada YRBS, 2019).”

Other Drugs

Other drug use has declined among Nevada youth over the past decade, except for marijuana. In 2017 use of the following drugs among Nevada high school youth was at or below 7.3%: cocaine, inhalants, heroin, methamphetamine, ecstasy/MDMA, synthetic marijuana, and steroids.

Less than eight percent of Nevada high school students have used:

- Cocaine (5.1%)

- Inhalants (7.5%)

- Heroin (2.6%)

- Methamphetamines (3.3%)

- Ecstasy/MDMA (6.3%)

- Synthetic marijuana (7.7%)

- Steroids without a doctor’s prescription (3.3%)

Source: Nevada Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Areas of Concern

Less than eight percent of Nevada high school students have used cocaine (5.1%), inhalants (7.5%), heroin (2.6%), methamphetamines (3.3%), ecstasy/MDMA (6.3%), synthetic marijuana (7.7%), or steroids without a doctor’s prescription (3.3%). Less than three percent (2.6 %) of students reported injection drug use. However, over one in four students (28.4%) reported that they had been offered, sold, or given an illegal drug on school property during the 12 months preceding the survey. This question has been a part of the core YRBSS questionnaire since 1993. With the legalization of both medical and recreational marijuana over the past two decades, student responses may not include marijuana as “an illegal drug.” Regardless of technicalities nearly 30 percent of Nevada students have the perception of access to illegal drugs on school property, a rate that is significantly higher than the national average of 19.8% (CDC YRBSS, 2017).

Additionally, almost one-third of students reported that they had ever lived with someone who was a problem drinker, alcoholic, or abused street or prescription drugs. The experience of living with someone with a substance use disorder qualifies as an adverse childhood experience (ACE) under the household dysfunction category (Felitti et al., 1998). This health risk is not currently monitored by the CDC at the national level.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) is the term used to describe all types of abuse, neglect, and other potentially traumatic experiences that occur to people under the age of 18. Adverse Childhood Experiences have been scientifically linked to chronic health conditions, low life potential, risky health behaviors, and even early death (CDC, 2019). The risk of adverse outcomes increases with the number of ACES and individual has experience before the age of 18. (CDC, 2019). The original groundbreaking ACEs study conducted in Southern California and published 1998 listed the 10 specific types of ACES organized by the following categories: Exposure to Abuse (psychological, physical abuse or sexual abuse), and Exposure to Household Dysfunction (mental illness, suicidality, criminal behavior resulting in incarceration, mother treated violently, substance abuse). The ACEs inventory has since come to include physical and emotional neglect and parental discord (Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, & Hamby, 2015). For additional information on the ACEs study and its implications for public and behavioral health, see the CDC’s ACE Study website.

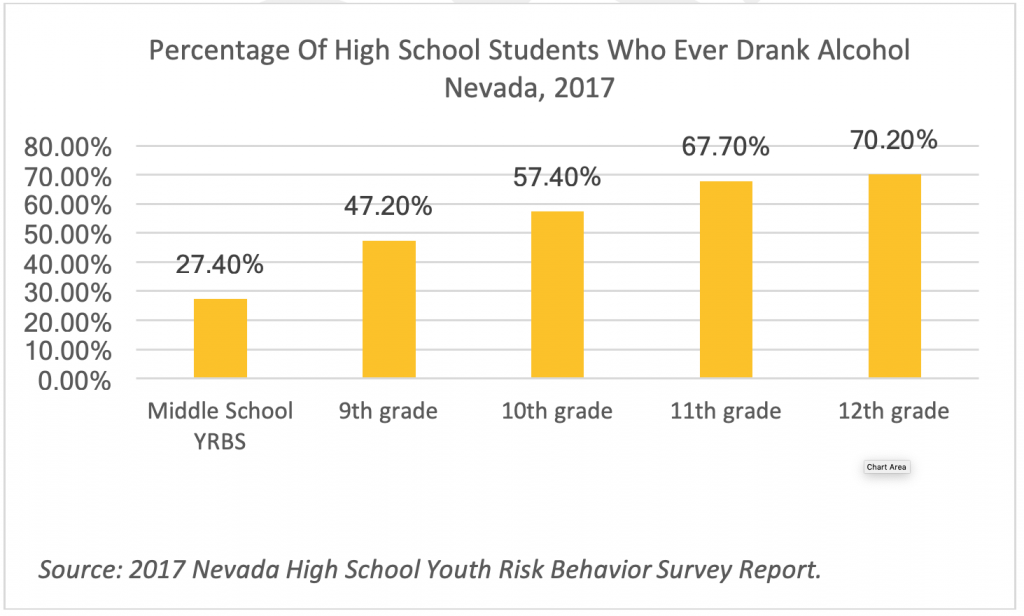

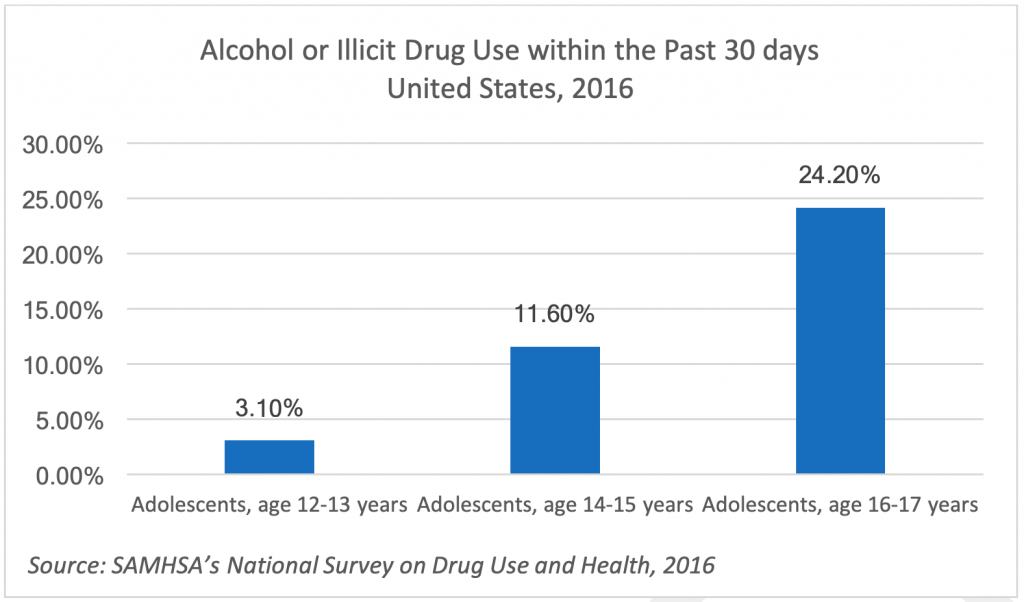

Despite the declines in overall use, (and in keeping with trends at the national level) Nevada youth use of alcohol and other drugs increases steady with age/grade level (see Figures 7 and 8 ).

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

Marijuana Use

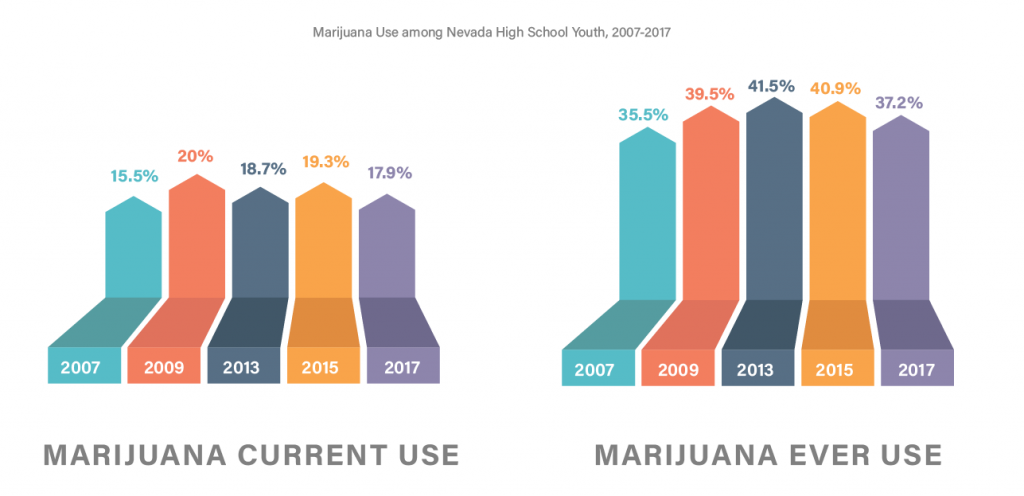

Marijuana is the one substance in the YRBS “Other Drug” category that continues to be consumed by Nevada youth at approximately the same rates year after year (no statistically significant differences; see Figure 9). Medical marijuana was legalized in Nevada in 2001, state-certified medical marijuana establishments became operational in 2015, and recreational marijuana for adults 21 and older became legal on January 1, 2017 (State of Nevada, n.d.). As with alcohol, marijuana use by Nevada high school youth increases with age and grade in school (Nevada 2017 YRBS).

Figure 9. Marijuana Use among Nevada High School Youth, 2007-2017

Source: Nevada Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Impaired Driving

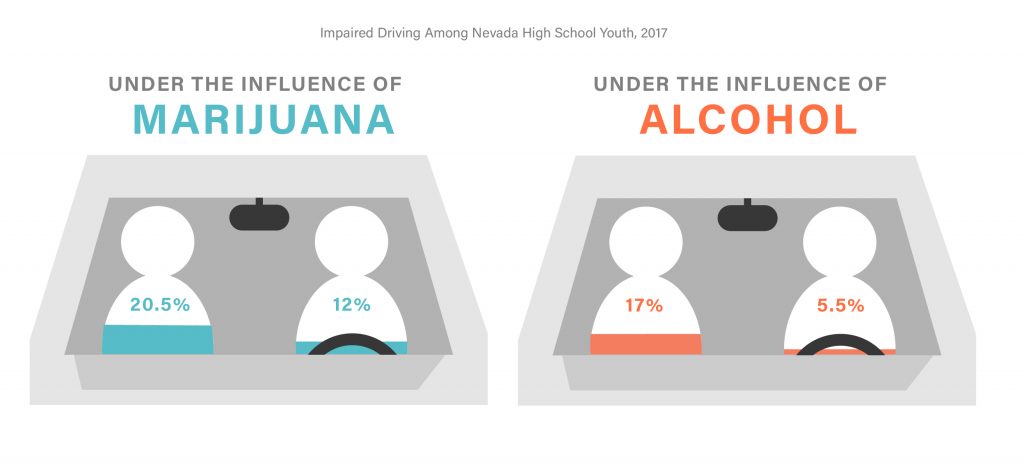

In 2017, Nevada high school students were more than twice as likely to operate a vehicle/drive while under the influence of marijuana (12%) than they were to do so under the influence of alcohol (5.5%). They were also more likely to ride in a vehicle driven by someone under the influence of marijuana (20.5%) than they were to ride with when the driver was under the influence of alcohol (17%) (see Figure 10). This may indicate a reduced perception of harm related to marijuana that does not align with the injuries and fatalities associated with driving under the influence.

Figure 10. Impaired Driving Among Nevada High School Youth, 2017

Summary

Nevada has made tremendous strides in the reduction of substance use among high school youth over the past decade (see Table 2). Rates of consumption for alcohol, cocaine, inhalants, heroin, methamphetamine, ecstasy/MDMA, synthetic marijuana, and steroids have all declined over the past decade. However, while traditional cigarette use had gone down, the emergence of electronic vapor products presents a new challenge to the health and wellness of Nevada youth. Whether use of ENDS is increasing or remaining steady with the introduction of Juuls, will be apparent in the 2019 data results. Rates of marijuana consumption among youth have remained steady for over a decade despite prevention efforts. It remains to be seen whether the recent legalization of recreational marijuana in Nevada affects the rates of youth use reported in 2019.

Table 2. Nevada High School Youth Substance Use 2007-2017

| Consumption Patterns -Reduced |

| Alcohol Cocaine Ecstasy/MDMA Heroin Inhalants Methamphetamines Steroids without a doctor’s prescription Synthetic marijuana Tobacco |

| Consumption Patterns -Maintained |

| Marijuana |

| Consumption Patterns -Increased |

| Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS), Vaping |

While celebrating Nevada’s ten years of progress in the overall reduction of youth substance misuse and abuse, it is important to remain vigilant with respect to new threats and rates of underage consumption of marijuana, which has been shown in longitudinal studies and brain imaging to have deleterious effects on adolescent brain development (National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), 2018). Trends such as the increase in consumption by age and grade level and availability of drugs on school grounds can also inform targeted prevention efforts.

Nevada prevention professionals continue to engage in coordinated efforts to reduce youth use of Marijuana and ENDS as well as prevention efforts aimed at all substance misuse and abuse to avoid the notorious pendulum swing of outcomes that can result from temporary and exclusive focus on one or more specific substances. Furthermore, Nevada YRBS researchers and steering committee members pioneered the inclusion of questions related to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in 2015. Understanding the data related to ACEs and other trauma indicators is critical to the work of individuals in the fields of health, public health, prevention, education and to communities at large (Courtney & Cappello, 2019).

Stay tuned for future blog posts related to Nevada’s state and federally funded prevention programming and the 2019 Nevada YRBS results.

References

Clements-Nolle, K. & Rivera, C. (2013). The epidemiology of adolescent health, Handbook of Adolescent Health Psychology. Springer New York.

Courtney K.O. & Cappello, D. (2019). Anna, age eight, the data-driven prevention of childhood trauma and maltreatment. ISBN-13: 978-1979903073, ISBN-10: 1979903077. Free download available at https://www.safetyandsuccess.org/download-all

Felitti, J., Anda, R, Nordenberg, D, Williamson, D., Spitz, A., Edwards, V. … Marks. J (1998).

Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-58

Finkelhor, D. Shattuck, A., Turner, H., & Hamby, S. (2015). A revised inventory of Adverse

Childhood Experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect 48, 13– 21.

Hawkins, J.D. and Catalano, R. (2005). Investing in Your Community’s Youth: An Introduction to the Communities that Care System, 2005 Edition (Item #501968D-07-05). Communities that Care System, 2005 Edition (Item #501968D-07-05).

Nevada Youth Risk Behaviors Survey (2018). University of Nevada Reno, School of Community Health Sciences, Research Activities, Nevada Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Retrieved from: https://www.unr.edu/public-health/research/yrbs

State of Nevada. (n.d.). Marijuana in Nevada Retrieved from http://marijuana.nv.gov/World Health Organization (2018). Adolescent health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/adolescence/en/

Great article!