The Many Facets of Compassion Fatigue & A Promising Intervention

Editor’s Note: This post has been updated and republished. To read the updated version follow this link.

Most people who work in human services, or care for other people (i.e., family caregivers) are familiar with the term compassion fatigue. Beverly Kyler, author of Surviving Compassion Fatigue: Help For Those Who Help Others, states that “compassion fatigue is a potentially devastating syndrome that impacts people physically, mentally, and emotionally, and results from absorbing and internalizing the emotions, pain, and suffering, others.” She explains that historically there have been several terms to describe compassion fatigue which include “secondary traumatic victimization”, “secondary traumatic stress”, “vicarious traumatization”, and “secondary survivor syndrome”. In recent years, psychologist have argued that the term used to describe the experience resulting from caring for others, should be “empathy fatigue”, as what is affected is a person’s ability to care (for self and others). Further, those who argue for the term empathy fatigue claim that most assessment tools are measuring empathy and not compassion.

Regardless of which term is used – each one is pointing to the cost of caring. According to Debbie Stoewen (2020), “Compassion fatigue is insidious.” Stoewen says that the most classic symptom is a decline in the ability to feel sympathy and empathy, along with an ability to give another compassion, which she describes as an action. She explains that sympathy says, “I care about your suffering”, while empathy is “I feel your suffering” and compassion is “I want to relieve your suffering”. With compassion fatigue, the caring, feeling, and acts of compassion decline. What’s oftentimes left is a sense of feeling detached. This detachment often influences every dimension of our life. Here is a look at how each dimension of wellness (physical, emotional, social, occupational, intellectual, and spiritual) may be influenced by compassion fatigue.

Physically one may experience:

Physically one may experience:

- Physical exhaustion

- Aches & pains

- Headaches & migraines

- Dizziness

- Nausea & vomiting

- Trouble breathing

- Impaired immune function

- Increased heartrate

- Appetite changes

- Sleep disturbances

- Nervous system on hyperdrive

- Increased use of substances to dull emotional pain

Emotionally one may experience:

Emotionally one may experience:

- Irritable

- Anxiety

- Anger

- Rage

- Resentment

- Numbness

- Overwhelmed

- Fear

- Depression

- Numbness

- Depleted energies

- Sadness

- Survivor’s guilt

- Blaming

- Mood swings

- Feelings of inadequacy or helplessness

Occupationally one may experience:

Occupationally one may experience:

- Low morale

- Avoiding certain tasks

- Obsessing about certain details

- Apathy

- Decreased motivation

- Negativity

- Diminished joy in work

- Detachment

- Decrease in commitment to work

- Conflict with colleagues

- Absenteeism

- Easily irritated

- Withdrawal from colleagues

- Loss of confidence

- Decreased sense of personal accomplishment

Socially one may experience:

Socially one may experience:

- Withdrawal from the people in your life

- Being overprotective

- Experiencing mistrust

- Decrease in sexual intimacy

- Isolation

- Projection of blame and anger

- Intolerance of others

- Judgement of others

- Loneliness

- Decrease in finding pleasure in activities

Intellectually one may experience:

Intellectually one may experience:

- Inability to concentrate

- Impaired Judgement

- Decreased problem-solving capability

Spiritually one may experience:

Spiritually one may experience:

- Loss of sense of purpose

- Anger towards God

- Questioning religious beliefs

- Loss of hope

- Feeling powerless

Compassion fatigue can touch every dimension of our life. As we look to ways to support ourselves when working with other people who are suffering, neuroscience has done some interesting research that is important to consider. Neuroscientist Tania Singer studied the difference between empathy and compassion in an EEG study of Buddhist monk Mattieu Ricard. When she asked him to listen to the distress of a woman screaming, the pain centers in his brain were activated, and he reported the experience as excruciating. Next, she asked him to practice compassion meditation (while his pain centers were still activated). When he did this the neural networks associated with love and positive emotions were also engaged. The shift in his attention allowed him to be aware of the woman’s pain, along with a sense of compassion for her suffering (Singer, T., 2012).

Dr. Kristin Neff (2015), recommends we practice compassion for ourselves, and the people we’re caring for in order to remain in the presence of suffering without becoming overwhelmed by it. In the case of compassion fatigue, it could also be described as a moment of suffering, and the practice of self-compassion is a viable intervention. The practice of self-compassion is described as compassion that is directed inward, and we are the object of our own care and concern. For many of us this may feel a bit foreign. We are often used to giving compassion to others, but we regularly leave ourselves outside of the circle of care and concern.

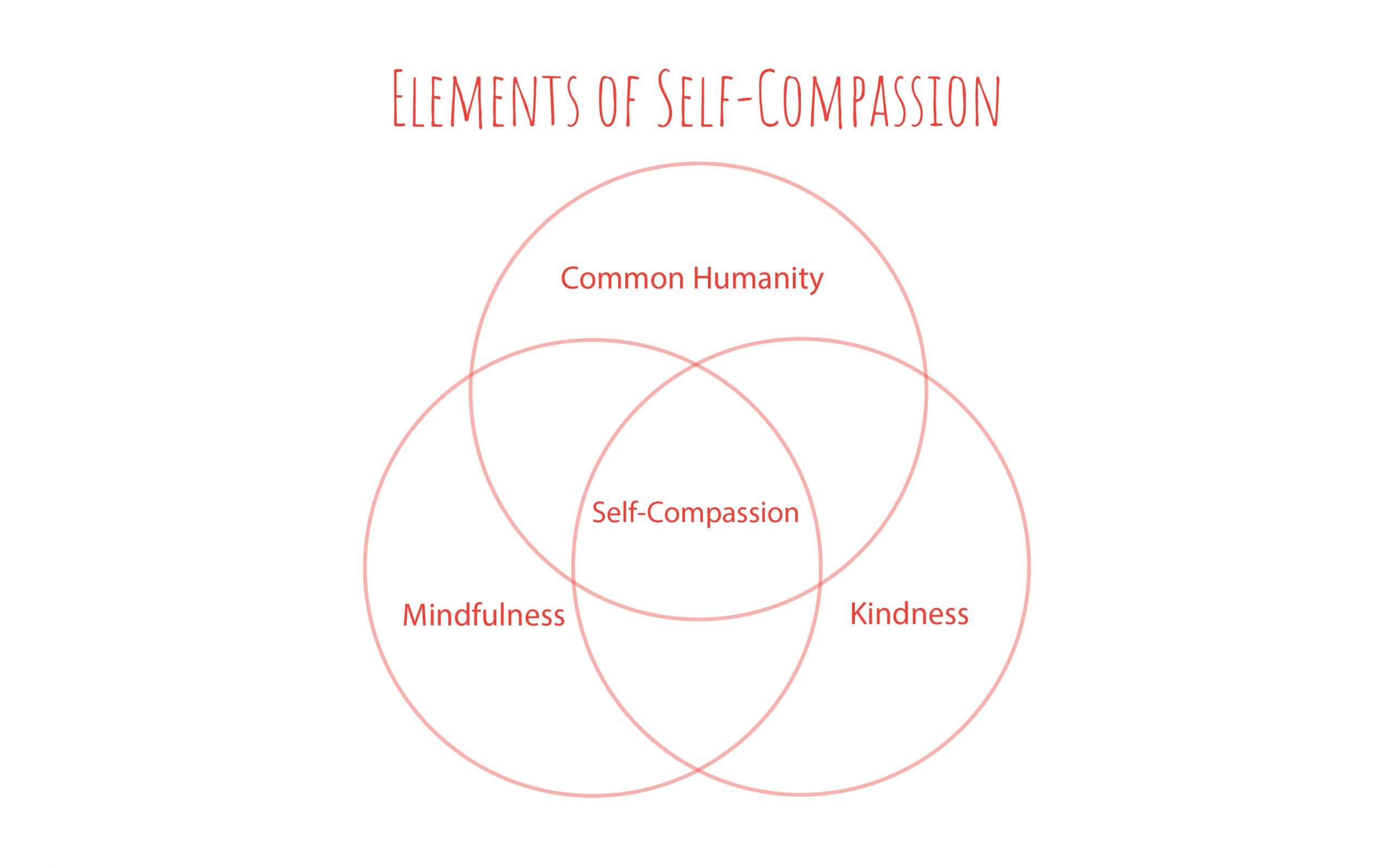

Self-compassion begins with mindfulness – or awareness of how we are feeling. It then recognizes our common humanity, and that everyone suffers at times in life, and lastly it requires an act of kindness (often a kind gesture with physical touch and/or word(s) of kindness) towards ourselves. Over time, practicing self-compassion helps us to increase our capacity to care. In addition, research has shown that self-compassion increases overall well-being; improves emotional intelligence; reduces depression and anxiety; increases resilience; increases optimism, wisdom, and motivation; and increases our ability to relate to others.

Self-compassion begins with mindfulness – or awareness of how we are feeling. It then recognizes our common humanity, and that everyone suffers at times in life, and lastly it requires an act of kindness (often a kind gesture with physical touch and/or word(s) of kindness) towards ourselves. Over time, practicing self-compassion helps us to increase our capacity to care. In addition, research has shown that self-compassion increases overall well-being; improves emotional intelligence; reduces depression and anxiety; increases resilience; increases optimism, wisdom, and motivation; and increases our ability to relate to others.

In summary, compassion fatigue decreases our ability to be empathetic and compassionate towards others. Through prolonged stress, and exposure to other people’s trauma we are susceptible to experiencing compassion fatigue. In addition, workload demands, inadequate rest between shifts, repetitive tasks, low control over job duties, decreased job satisfaction, poor recognition, and lack of support from supervisors and/or organization all increase a person’s risk for experiencing compassion fatigue. With up to 85% of people in human services experiencing compassion fatigue (Upton, K.V., 2018), it is an important consideration for anyone who works in human services.

In summary, compassion fatigue decreases our ability to be empathetic and compassionate towards others. Through prolonged stress, and exposure to other people’s trauma we are susceptible to experiencing compassion fatigue. In addition, workload demands, inadequate rest between shifts, repetitive tasks, low control over job duties, decreased job satisfaction, poor recognition, and lack of support from supervisors and/or organization all increase a person’s risk for experiencing compassion fatigue. With up to 85% of people in human services experiencing compassion fatigue (Upton, K.V., 2018), it is an important consideration for anyone who works in human services.

Ready to Learn More:

Listen to Season 4 of CASAT Conversations. Season 4 delves into the topic of secondary and vicarious trauma experienced by people who work in the field of human services. You’ll hear from researchers, authors, clinicians, and people with lived experience who share about the importance of this topic, along with ways to care for yourself, and the value of having a community of support. In each conversation, we hope you find a nugget of information that will support you in the work you do. Listen to episode 2 today! In episode 2, you’ll hear from Beverly Kyer, an author, speaker, and compassion fatigue specialist. She shares the wisdom she’s developed over the course of her career. You’ll hear about her own personal experience with compassion fatigue, along with her research, and how she now dedicates her career to helping those who help others.

Listen to Season 4 of CASAT Conversations. Season 4 delves into the topic of secondary and vicarious trauma experienced by people who work in the field of human services. You’ll hear from researchers, authors, clinicians, and people with lived experience who share about the importance of this topic, along with ways to care for yourself, and the value of having a community of support. In each conversation, we hope you find a nugget of information that will support you in the work you do. Listen to episode 2 today! In episode 2, you’ll hear from Beverly Kyer, an author, speaker, and compassion fatigue specialist. She shares the wisdom she’s developed over the course of her career. You’ll hear about her own personal experience with compassion fatigue, along with her research, and how she now dedicates her career to helping those who help others.

References

Almadani, A. H., Alenezi, S., Algazlan, M. S., & Alrabiah, E. S. (2022). Compassion Fatigue Among Practicing and Future Psychiatrists: A National Perspective. Cureus, 14(5), e25417. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.25417

Cocker, F., & Joss, N. (2016). Compassion Fatigue among Healthcare, Emergency and Community Service Workers: A Systematic Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 13(6), 618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13060618

Kilner, J. M., & Lemon, R. N. (2013). What we know currently about mirror neurons. Current biology : CB, 23(23), R1057–R1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.10.051

Neff, K. (2015). Why caregivers need self-compassion by Kristin Neff. Self-Compassion. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from https://self-compassion.org/why-caregivers-need-self-compassion/

Singer, T. (2012, April). Neuroscience, Empathy and Compassion. Paper presented at the International Symposia for Contemplative Studies, Denver, CO.

Stoewen D. L. (2020). Moving from compassion fatigue to compassion resilience Part 4: Signs and consequences of compassion fatigue. The Canadian veterinary journal = La revue veterinaire canadienne, 61(11), 1207–1209.

Upton, K.V. (2018). An investigation into compassion fatigue and self-compassion in acute medical care hospital nurses: a mixed methods study. Journal of Compassionate Health Care 5, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-018-0050-x

Blog Post Tags:

Related Blog Posts

Related Learning Labs

Related Resources

.

- Buscar Tratamiento de Calidad para Trastornos de uso de Sustancia (Finding Quality Treatment for Substance Use Disorders Spanish Version)

- Finding Quality Treatment for Substance Use Disorders

- Focus On Prevention: Strategies and Programs to Prevent Substance Use

- Monthly Variation in Substance Use Initiation Among Full-Time College Students

- The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Report: Monthly Variation in Substance Use Initiation Among Adolescents